Exploring the Entheogenic Underground: An Interview with Graham St John

Categories: New Release

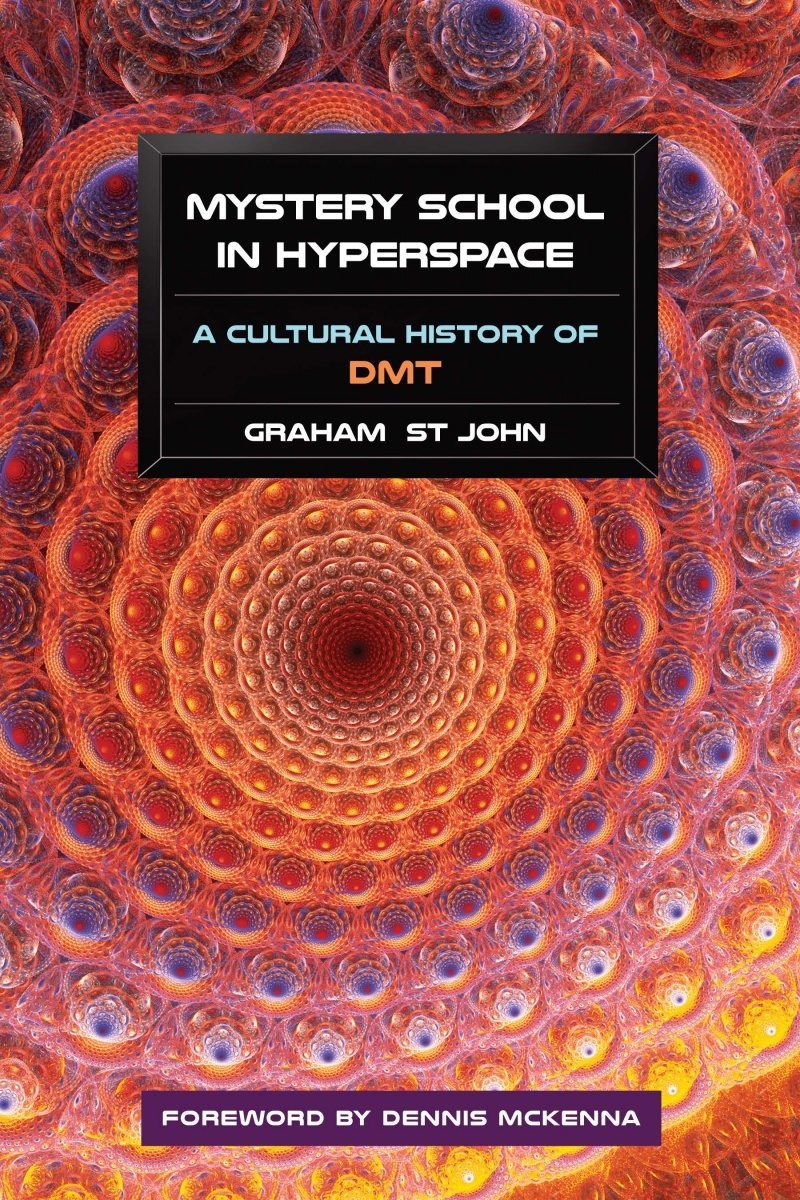

As advances are being made to lift the moratorium on human research with psychedelics, Mystery School in Hyperspace arrives just in time to join the conversation. Exposing a great many myths, this cultural history reveals how DMT has had a beneficial influence on the lives of the artists, scientists, and explorers who have worked with it, and whose reports and initiatives expose drug war propaganda and shine a light in the shadows.

As advances are being made to lift the moratorium on human research with psychedelics, Mystery School in Hyperspace arrives just in time to join the conversation. Exposing a great many myths, this cultural history reveals how DMT has had a beneficial influence on the lives of the artists, scientists, and explorers who have worked with it, and whose reports and initiatives expose drug war propaganda and shine a light in the shadows.

Regarded as the “nightmare hallucinogen” or celebrated as the “spirit molecule,” DMT is a powerful enigma. In Mystery School in Hyperspace, cultural anthropologist Graham St John excavates the significance of this enigmatic phenomenon in the modern world. Here, he answers a few questions for us about his newly released book.

NAB: Can you tell us what the title of your book, Mystery School in Hyperspace, refers to?

Graham St John: It denotes the effect of DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) as reported among a growing population of users. Many claim that use expands consciousness and perception enabling access to higher, other, or parallel dimensions. Transdimensional or not, as reported within a global networked research community, this quintessentially liminal space-time, typically referred to as “hyperspace,” is reported to involve profound changes in consciousness, visionary states, and contact experiences. The book charts the contours of DMT space through the exploits of advance parties and quality surveyors, and along the way traces the concept of nth dimensional “hyperspace” in esoteric, occult, and science fiction currents.

What drove you to study DMT?

In short, one of humanity’s greatest mystery thrillers: the enigmatic character of a compound that is today among substances of the fastest growing interest and yet it continues to defy explanation. DMT has been something of a “holy grail” for seekers since Stephen Szára discovered its psychopharmacological actions in 1956, and yet this compound has been largely undocumented, certainly in the fashion that other substances living in the shadows of the War on Drugs have suffered. While there is, for instance, a library of works now available on LSD (its scientific discovery and its artistic and cultural impact), the DMT shelves are comparatively sparse. I was intrigued as to why this is the case. So the book can be figured as a sort of detective story. It’s incomplete as far as such stories go (after all it is “a” history of DMT not “the” history), but the book offers various explanations for DMT’s mysterious status, without claiming to uncover its mystery once and for all. This project required diving into the history of the quest to understand what DMT is. So the book documents a litany of seekers, from Burroughs to Nick Sand, Leary to the McKennas, Rick Strassman to Alex Grey, and many contemporary practitioners and inventors who populate the entheogenic underground, who’ve sought to discover new and varied truths about reality, nature, and consciousness through the use of DMT.

Along this journey, I discovered that we hold a most ambivalent attitude towards DMT, a compound inciting fear or evoking hope, suffused with danger or charged with love, with those who wish to prohibit or liberate it, vilify or champion it, restrict availability or augment effect, disputing its meaning and contesting its status. This book forges a path through this labyrinth.

What are the effects of DMT? Is this something people do for fun?

DMT is a potent short-lasting tryptamine that has seen growing appeal in the last decade, independent from ayahuasca, the Amazonian visionary brew of which it is an integral ingredient. Known to trigger out-of-body states, and to produce profound changes in sensory perception, mood, and thought, DMT has inspired an underground community of enthusiasts who typically embrace the “entheogenic” (i.e. awakening inner divinity) characteristics of this and other compounds. The book explores the propensities of the DMT trance, especially as characterised in the “breakthrough” experience, an event associated with entity contact, mystical experiences, and sometimes near-death experiences. The wider effects of these exceptional conditions is apparent in art, music, and culture, an aesthetic efflorescence that will continue to receive documentation as more reports surface.

DMT is a potent short-lasting tryptamine that has seen growing appeal in the last decade, independent from ayahuasca, the Amazonian visionary brew of which it is an integral ingredient. Known to trigger out-of-body states, and to produce profound changes in sensory perception, mood, and thought, DMT has inspired an underground community of enthusiasts who typically embrace the “entheogenic” (i.e. awakening inner divinity) characteristics of this and other compounds. The book explores the propensities of the DMT trance, especially as characterised in the “breakthrough” experience, an event associated with entity contact, mystical experiences, and sometimes near-death experiences. The wider effects of these exceptional conditions is apparent in art, music, and culture, an aesthetic efflorescence that will continue to receive documentation as more reports surface.

The question of DMT’s impact has deeper implications, since there are those who argue that the endogenous release of DMT in the human brain has had a significant impact on the development of religion, culture, and consciousness throughout history. These are the startling implications of Rick Strassman’s research at the University of New Mexico in the 1990s in which Strassman made speculations concerning DMT’s status as the “spirit molecule,” the “brain’s own psychedelic.” While Strassman led research into the role of DMT in extraordinary human experiences (i.e. those associated with birth, death, and paranormal states), others conduct research into the role of DMT in normal metabolism, perception, and somato-physiological functioning. Regardless of its actual role, DMT’s endogenicity suggests that it is not a question about whether we “do” DMT at all (in the way that, for instance, one takes a drug), but about whether DMT does us.

How has our understanding of DMT changed since its action was discovered by scientists in the ’50s and ’60s?

From “terror drug” or “metaphysical reality pill,” a cornucopia of labels circulating since the 1950s reveal the disputed legacy of DMT. Although variously interpreted, DMT’s endogenous status—i.e. that the compound occurs throughout nature and is present in the human brain, binds to brain receptor sites, and resembles the neurotransmitter serotonin—has been a cause for considerable excitement. But the compound has worn various hats since the 1950s, when a prevalent perception among psychopharmacologists and psychiatrists was that DMT was a “psychotomimetic” (which like LSD was said to model mental illness) or “psychotogen” (i.e. an endogenous chemical that causes mental illness). Before it was subject to prohibition, the “psychedelic” label (i.e. a substance that expands the mind) came into vogue. The popular perception among contemporary users is that DMT is an “entheogen” (i.e. a substance that “awakens the divine within”). But while there are many substances and techniques that have been regarded as “entheogenic,” the unique status of DMT is that it is naturally present in humans, unlike LSD for example, a circumstance inspiring Strassman’s research.

DMT is classified as a “Schedule I” substance in the U.S. This means that it possesses no accepted medical use, and is recognized to have a high potential for abuse. Do you think this classification is justifiable?

Terence McKenna once stated to an audience: “At this moment you’re holding a Schedule I drug and are subject to immediate arrest and trial.” Prevalent scheduling systems may deserve to be pilloried, but we should also take stock of their impact, especially given the restrictions placed on research that could lead to truth claims challenging those currently enshrined in law.

The official position is that DMT and its analogs are dangerous and possess no medicinal value, often classified in the same class as heroin, cocaine, and other drugs of addiction. This situation is absurd, especially given that laws prohibit not only personal use, but place heavy restrictions on research into the phenomenal and subjective effects of this substance—a substance that we know occurs naturally inside us, but which we know surprisingly little about. We remain in a dark age of science in this regard. How can we know a substance has no scientific value if we close it off to research, or discourage such research? This is effectively our situation today, despite the gains made in some areas, the accumulation of which has been celebrated as a “psychedelic renaissance.” According to many practitioners, rather than possessing no medical value, among various uses, DMT and its analogs might very well offer a remedy for the modern affliction of alienation.

What has been the impact of prohibition?

Other than the restrictions on personal use and research, prohibition has crystalized an underground research community. Since the mid-1990s, the collective efforts of an independent movement has brought illumination to, or at least colored, the long shadows under prohibition. First through The Entheogen Review and later virtual platforms like the DMT-Nexus, and a host of other webforums, an underground community of mind experimentalists, consciousness hackers, and botanical code breakers have networked to exchange tripping reports, optimized synthesis techniques, botanical discoveries, and methods of extraction and sustainable plant propagation, along with augmentation alchemies and guidelines for safe practice.

Can you explain where the research for this book took you, and the kinds of people you met along your way?

This project led me into the path of many artists, scientists, and pioneers working with this compound. Chief among these are the McKenna brothers, who trekked to the Columbian Amazon in 1971, the site of the infamous “experiment at La Chorrera,” in the wake of which they would lead dramatically varied careers: Terence, a loquacious frontman for the “machine elves of hyperspace,” Dennis, a renowned ethnopharmacologist. Although Terence passed to the next level in 2000, the dramatic doyenne of psychedelic hyperspace philosophy remains very much alive today, if the profusion of spoken-word performances permeating cyberspace and programmed track samples are any measure. He is among the chief inspirations for the book which attempts to capture Terence McKenna’s contemporary animation. To that end, I was aided by Dennis, who introduced me to Terence’s high school pal Rick Watson. As recounted in the book for the first time, Watson introduced Terence to DMT in 1965, and by virtue of that, the machine elves, whose visitations had such a compelling influence on Terence, and, subsequently, many others.

But that story is one thread in a bristling thicket of narratives, each which animates the lives of inspirational experimentalists and innovators whom I encountered during the research for this book. The intriguing research efforts of a spectrum of scientists are taken up, not least of which is the work of Rick Strassman and the strange-but-true career of the “spirit molecule.” The story arc of the “DMT gland” is documented as Strassman’s speculation that DMT is sourced from the brain’s pineal gland—effectively oiling the hinges on the gateway between matter and spirit—left the clinic and took up an independent career in popular culture. Other threads wind through the research underground, where we take up the story, for instance, of pioneers like creator of DMT smoking blend, changa, Julian Palmer.

Recounting the adventures of hyperspace surveyors and charting their breakthroughs in tryptamine liminality, the book composes a transdimensional odyssey as found, for instance, in the tryptamine aesthetic of “the man who can dig it,” William S. Burroughs, the “experiential language” of Leary, the vibrant x-ray art of Alex Grey, or in cinema like Gaspar Noé’s perverse epic Enter the Void. It explores how DMT has inspired musicians from the 1960s to the present, from psychedelic rock to psychedelic trance, dubstep to country, experimental electronica to metal. From Roky Erickson of The 13th Floor Elevators, to Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, to Shpongle cofounders Raja Ram and Simon Posford, musicians have been compelled to craft soundscapes inspired by their outlandish adventures in DMT space. Not least among them is founder of Dragonfly Records Youth (Martin Glover) who recounts how his experience with DMT gave birth to psychedelic trance.

What is the meaning and significance of so-called DMT entities?

DMT space possesses extreme variability, perhaps most clearly echoed in the phantasmagoria of reported entity encounters: a veritable transdimensional bestiarum, from teacher to archon, trickster to benevolent alien, machine elf to organic insectoid, monster to mother. The study of entities (like the study of UFOs) and speculations concerning their origin, meaning, and purpose gives way to a flood of insights on the nature of consciousness. Whether these are beings from higher dimensions or parallel universes, spirits of the dead, divine intermediaries of God (if not the creator him- or herself), archetypes from the collective unconscious, important messages communicated from our DNA, time travelers from the future, perinatal or past life phenomena, or simply hallucinations shedding light on the nature and serviceable logic of mystery, as this book illustrates, the answers probably won’t arrive anytime soon. But, if nothing else, DMT is good to think with. While ultimately elusive, the cause appears less important than the effect. This was Terence McKenna’s insight with regard to UFOs, as it surely will have been that of William James. It is not what they are that ultimately matters, but what they can do for us. This sentiment rings true for the cognate anomalies that are DMT entities. Rather than ask where they come from, it appears more fruitful to explore, whether on a scale of personal growth or consciousness evolution, the meaning and implications of the message.

You describe several theories about consciousness as it relates to DMT—how do you weigh in on these?

Mystery School in Hyperspace is an exploration of the potency of DMT and its analogs. The potential of DMT, as indeed of all psychoactive tryptamines, resides in its impact on consciousness: its effect on consciousness and the way this impact makes possible a transformed understanding of consciousness. That is, DMT’s capacity to trigger profound changes in consciousness has a tendency to potentiate transformed knowledge of consciousness. The exposure that is sometimes referred to as the “DMT flash,” may prompt experients to question the physicalist perspective in which the brain is reckoned to be the vessel of consciousness (and not, for example, a receiver of consciousness). Time and again, the phenomenal experiences occasioned by DMT lead users to adopt, affirm, or even recall perspectives in which experients accept that this is not all there is.

Read more from Graham St John now in the new book Mystery School in Hyperspace!

Read more from Graham St John now in the new book Mystery School in Hyperspace!