Sometimes it takes a while to see the box you’ve been living in.

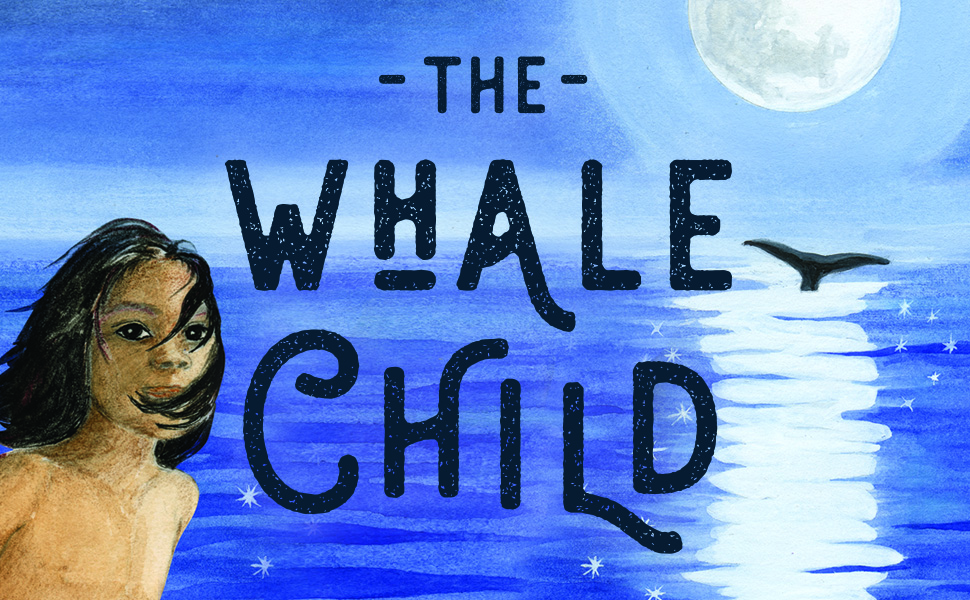

Such was the case for North Atlantic Books with Keith and Chenoa Egawa’s poignant children’s book The Whale Child, which we released together on October 13, 2020.

The book had first come to our attention over three years prior when a freelance editor we work with had recommended we give it a look. We were deeply impressed with the art and the writing assembled by this Coast Salish brother-and-sister team and knew the message was powerful: that solving our planetary crisis requires an understanding of our interrelations with other species and Earth as a living creature. And that this understanding, while urgent, is not new and is in fact a central part of Indigenous cosmologies that have existed for millenia.

At that moment in North Atlantic Books’ history, we were struggling to decide whether to continue publishing children’s books. We had published a few dozen over our forty-five-year history, but most of them had struggled to find an audience. We knew from experience that children’s literature is a challenging genre; there are tens of thousands of children’s books published every year, and it is one of the more “laned” categories in publishing: parents and teachers expect certain formats for certain age ranges, and books that defy these norms often end up lost in the sea of books clamoring for children’s attention.

Keith and Chenoa’s book wasn’t conventional in its format: it featured beautiful full-color art, which could have lent itself to a picture book for younger readers, but the story was nuanced, detailed, and definitely too long for a picture book. The truth is that it took this kind of length and breadth to convey the story of a whale child who is transformed into a boy so that he can communicate to his human family on land the severity of the planetary crisis. But most children’s books of this length, conventionally, are prose-y chapter books intended to draw newly independent readers in with flashy characters and quirky twists and turns. The Whale Child was dramatic, but it was serious, and it was ultimately grounded in a mission of changing the world.

The Whale Child was, in other words, a curve in a right-angled landscape, and we didn’t have the confidence and courage at the moment to take it on. And so we let the project go.

Two years later, as our own organization went through monumental shifts as a result of racial -equity work, I began to see more and more how rigid categories and even “best practices” are often code for maintaining norms that uphold systems of oppression rather than challenge them, especially in a publishing industry that is overwhelmingly white, both in terms of personnel and who gets published. As my racial-equity lenses became sharper, I began to see how “perfectly logical explanations” for certain choices were in fact cop-outs that maintained white supremacy’s hegemony, from publishing decisions to hiring practices. I could feel myself growing out of the paternalistic limits placed on my ability to imagine and create different futures.

And so I turned back to our archive and read The Whale Child again from start to finish. What a revelation it was! I still saw the way it didn’t fit neatly into one category, but this time I understood that not as a liability but as an asset. Haven’t most barriers been brought down by movements and expressions originally dismissed as outliers or even blasphemies? Couldn’t our planetary crisis, which has generated only marginal change in human behavior despite its urgency, use a little blasphemy?

I contacted Keith and Chenoa on the off chance that the book was still unpublished and that they would be open to working with us. Fortunately, for North Atlantic Books and the world, Keith and Chenoa were receptive to the dialogue. This time, instead of trying to make the book fit into a category, we celebrated its idiosyncrasy, doubling down on the faith that a beautifully illustrated book with a nuanced fictional story about Indigenous philosophy and ecological care could and would be embraced by seven- to twelve-year olds eager to read this kind of book on their own. Assuming this young reader was intellectually curious, we worked with the Indigenous scientist and scholar Jessica Hernandez to supplement Keith and Chenoa’s work with an educational-resource section, where the reader who has just been moved by the story can learn more about Pacific Northwest Indigenous cultures and the environment.

In the end, perhaps it is our children who best intuit the gravity of the planetary crisis. We will be fortunate if we get the chance to follow their lead. It is my sincere hope that they will find more and more books that meet them where they actually are, which is usually beyond the confines we have socialized them into.

And so far, the critics seem to agree. Kirkus Reviews, known in publishing circles for its tough assessments, said of The Whale Child in its starred review: “By relating the tale through the eyes of children, the author-illustrator team evokes an empathy that should stir a wide audience. This necessary read decolonizes the Western construction of climate change.” May we all wake up to the new geometries.

—Tim McKee, publisher of North Atlantic Books