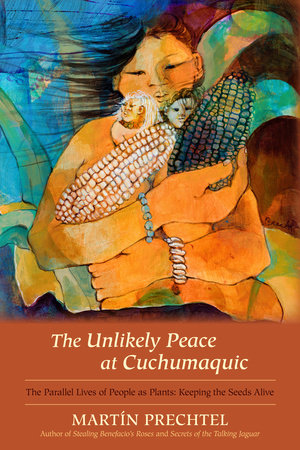

Below is an adapted excerpt from Martín Prechtel’s The Unlikely Peace at Cuchumaquic, a book that chronicles the author’s incredible journeys in a genre-defying format that’s part myth, part lyrical memoir, and part cultural commentary. In keeping with June’s themes of growth, rites of passage, and coming into oneself, we’ve selected a counterbalance to the popular conceptions of success, challenging the importance we place on competing for winning’s sake. Here, Prechtel poetically illustrates the importance—and power—of different ways of approaching knowledge, community, tradition, and intention.

Always a Place at the Table

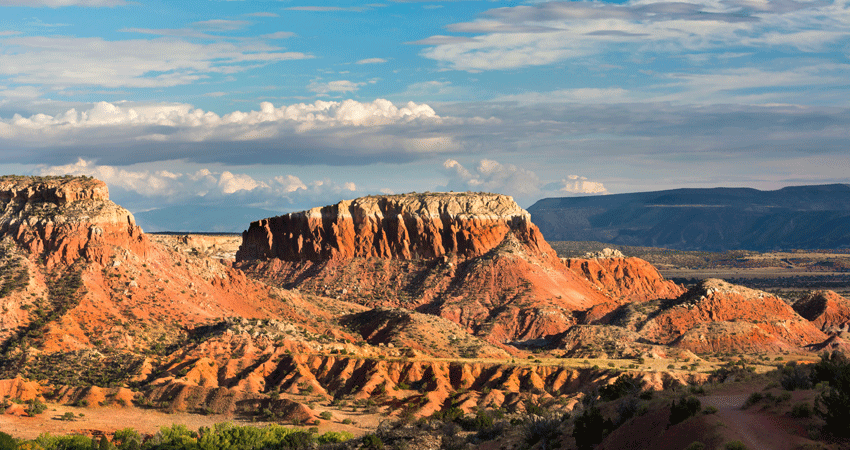

As young children on the reservation I remember the deep need to run. For all the young Indian people, both girls and boys, running was as great a characteristic of the Indigenous life of Pueblo, Navajo, and Apache people still living in their original beloved homelands of the arid highlands of New Mexico as was their sense of comic joy or the generous ceremonial house-to-house feasting throughout their villages, for which they are still famous.

Like all of the English-speaking public schools in the United States that Native and Spanish-speaking children of our area were forced to attend, there were always kids in the sixth grade old enough to drop out of high school, for it was they who were the first generation of minors in their family lines to be enforced by federal law to begin school attendance, no matter what their age. Characterized as arrogant, troublesome, and incapable of learning, they were actually not slow, and certainly no more incorrigible than the rest of us. School for them was an imposed irrelevancy to the reality of their already adultish life they led inside “their” own natural Native territory. They, of course, felt no compelling responsibility to attend an invader’s academy that had so little to teach them in reference to what they already knew and would need to live regarding village planting, hunting, courting, and their constant obligatory communal ceremonial participation upon which old-time Pueblo life has always relied and which was still a going concern in my youth.

The casual special appearances and unauthorized disappearances to and from the classroom of these beautiful, rowdy older teenagers ran pretty much according to how they rated the entertainment value of the few chosen teachers whose method of instruction appealed to them. School authorities learned early on that these students could never be threatened with expulsion for they would have loved nothing better. But there was one aspect of the school that no student ever missed, unless impeded by mandatory village ceremonial obligation, and that was a footrace of any distance scheduled by the coaches.

To be truthful, they couldn’t have given a flea’s fart for the racing. They didn’t come to race; what they loved was running, running across their own rolling wild homeland, just for the deliciousness of running enormous distances through the sacred itself. Like the feral multicolored horses, wild antelopes, jackrabbits, and swallows that coursed along with them, they too were made of elegant motion and just had to do it. In the same way breezes can’t help but sweep the earth, they had to run. It was a delicious ancient inborn itch that paced in the hearts of their Indigenous Souls that would only be calmed by running, and running well and beautifully.

The school sports coaches like most of the world anymore were representatives of that neurotic, competitive, need-to-dominate culture trait that characterizes most large civilizations, and they always felt like they’d failed in life unless they could conquer someone else. They needed to win, needed to cause someone else to lose. That’s all they understood. But in our school they lived in a constant tangle of nervous frustration. The source of their consternation was rooted to the unshakeable fact that even though most of these Indian boys over thirteen had running times superior to those of adult Olympians worldwide, they could not be made to compete. They just wanted to run, and run at home over the wild unpopulated land.

Like a lot of teachers in other departments, these tall non-Indian jocks became so infuriated about how they could never get the Pueblos or Navajos to compete in any tournaments that before the inevitable tendering of their resignations, they usually transformed into bitter listless maniac whiners who labeled the Indians as “unconfident,” “overly shy,” or “ashamed,” or as most of us heard over and over again: “Indians are an unmotivated race lacking the “go-getter gene,” i.e., competitive “ambition.” The coaches couldn’t believe the reality that all the young people, like their ancestors forever, just loved running, not racing. This didn’t mean they didn’t run hard and fast, because they did. However, they didn’t do so to beat a peer, but because hard and fast was part of the deliciousness. Though their short-distance times were very good, where the natural peoples of this state of New Mexico excelled was in long-distance running. The young men would run 10,000 meters, or ten miles, or four miles, whatever distance was designated as a “race,” sometimes even stopping off somewhere to chat or check something out, always in a group, joking as they ran . . . and still come in well under international times, that is, if the coaches could have convinced them to cross an assigned finish line, instead of just running off to smoke and gossip before they wandered in.

The other problem for civilization’s sports teachers and their need to win was the fact that though all the Indian boys ran good and hard they never ran alone, only as a group. If they happened upon a relative or friend along the way, they always urged them to run along with them, no matter how much slower a pace they might have to assume to let their older friend keep up—for such was the grand etiquette of Pueblo Indian togetherness. This meant if one of their group straggled, they would wait or run in circles not to lose momentum until the slower fellow caught up. This was definitely not conducive to an Olympic record, but a normal score for the generosity of the Indigenous Soul.

Even a couple of generations later when so much of the cultural intactness of those times had been successfully undermined and people were thoroughly indoctrinated with the syndrome of modernity’s contradictory insistence on an unquestionable superiority while suffering eternally from that hardwired shame of “never being good enough” that fuels civilization’s bullet train away from its own indigenous intactness, and after being successfully shamed into becoming as anxious as any Anglo about achievement, certain generations of young Indian men and women who’d been finally coerced into the nervous pride of home-and-away track meets, warm-ups, sweat suits, shorts, numbers, running shoes, trophies, victory dinners at Burger King and, God help us all, recognizing a finish line, would often even then stand jogging just before the finish line after running several miles ahead of everyone if one of their relatives was a participant in the same race and needed more time until he caught up in order to cross the line together. Even after so much assimilation, it still felt awful to do otherwise!

But the best long-distance running I ever saw at that school happened when the heroes of my youth—a group of boys, famous runners all of them, about sixteen years old, several already married, but all of them still in the sixth grade—agreed to run in their first competitive long-distance races. One of our more sneaky and desperately determined coaches secretly marked the finish line with chalk about two hundred yards beyond where it would actually lie by official track standards in order to get the kids running hard across the invisible real line without lagging for the slower ones. But he was outwitted yet again. This had been a 10,000-meter race on the reservation against teams from many other places. When the five boys came leisurely striding in at least a mile and a half ahead of all the visiting runners and while casually sharing their third disqualifying Camel cigarette as they sailed along, they not only technically won a world record that would still hold today if it had been accepted on the basis of time alone, but then after unknowingly having crossed the secret finish line together, in order to avoid what they thought was the marked finish line, these copper-bodied human birds took a collective left and just kept running and coursing the remaining five-and-a-half miles back to their home village through the beautiful high-piled boulder desert hills and sandy arroyos in blossom with the wild parsley and four-petaled yellow mustards of spring to disappear utterly from the white man’s world, their school, and its program of achievements, running straight into the initiation kivas where they began their antique lives cloistered again as Pueblo Indians for the rest of their adult lives. Three of them are there to this very day.

Living and running were holy things you were supposed to get good at, not things to use to conquer, win, and get attention for. Running was not meant for taking but for giving gifts to the Holy in Nature. Running was an offering, a feeding of life.

This sometimes humorous but always devastating cultural collision between the need to conquer against the need to feed and give gifts was never more acutely visible to me than it was during ceremonial Pueblo Indian footraces.

These are ritual cross-country races between people born for the powerful gods and goddesses of summer deities and people born for the winter deities. They were run by young men, men newly initiated who of course ran in groups as the champions of the distinct gods they served.

A lot of people always gathered to watch and pray for the well-being of the runners and themselves. In some less traditional, not-so-strict places, non-Indians, non-tribal friends, were invited and fully welcomed to watch. Though this welcome was never extended to any outsiders in my area, there was no ban on our visiting other, more open, villages.

One time while visiting with some friends who had a relative married into a less guarded Pueblo village up the river, a little outside the pueblo we gathered with all their female relatives, sisters and sweethearts, with supporters of each side to encourage them on.

After the fifteen of the Moon side of summer got a strong takeoff running against the forty or so of the winter Sun, the visiting tourists shouted and continued cheering in that adamant well-practiced way as they would at all their competitive events as the painted boys disappeared into the wild. But this was Indian running and therefore cross-country, with long distances; therefore most of it was out of sight. So as soon as the young runners hit the rings of grama and clumps of buffalo grass, the chollas, the sabinas, and boulders of the uncultivated area and were out of earshot and into the dust-whipping spring wind, the villagers in the supporting crowd walked briskly back to their houses to get on with the traditional feast, leaving the still-cheering tourists alone and baffled as to what had happened.

Some of the good-hearted “white people” made their way with the rest of us to houses where feasts had been prepared, invited there by the parents and godparents of the runners. When the old people were asked by the outsiders what happened to the runners, they were courteously informed that they were probably running—and would the visitors please sit down and eat with them? Such feasting was not only an honor for visitors and one that was expected in the house of the family of the runners, an honor that comes with an obligation to accept whether or not one is hungry; it was a way for the non-running population of the village to magically give strength to the runners. This custom still lives on in every Pueblo to this day.

When further interrogated as to where the finish line was, the people usually said, “Wherever they stop running, I guess.” Maybe eventually a more compassionate and patient younger person would tell the visitors the truth. “There is no finish line, they’re just running.”

“How do they know who wins? How do they know when to stop running? Why do they run at all?”

The running of these young people was a grand thing and they, just like all the weather and every natural phenomenon, animal, plant, river, ocean, air, earth, every natural thing who each run their own races to keep all their own diverse particles of the magnificence of a world made whole and alive by doing so, the running boys would come in to the feast of life when it was time for them to come. And so it was, for when the race had subsided, each boy returned to his home and together we all ate the food that we all knew his running had kept alive.

Everything in Nature ran according to its own nature; the running of grass was in its growing, the running of rivers their flowing, granite bubbled up, cooled, compressed and crumbled, birds lived, flew, sang and died, everything did what it needed to do, each simultaneously running its own race, each by living according to its own nature together, never leaving any other part of the universe behind. The world’s Holy things raced constantly together, not to win anything over the next, but to keep the entire surging diverse motion of the living world from grinding to a halt, which is why there is no end to that race; no finish line. That would be oblivion to all.

For the Indigenous Souls of all people who can still remember how to be real cultures, life is a race to be elegantly run, not a race to be competitively won. It cannot be won; it is the gift of the world’s diverse beautiful motion that must be maintained. Because human life has been given the gift of our elegant motion, whether we limp, roll, crawl, stroll, or fly, it is an obligation to engender that elegance of motion in our daily lives in service of maintaining life by moving and living as beautifully as we can. All else has, to me, the familiar taste of that domineering warlike harshness that daily tries to cover its tracks in order to camouflage the deep ruts of some old, sick, grinding, ungainly need to flee away from the elegance of our original Indigenous human souls. Our attempt to avariciously conquer or win a place where there are no problems, whether it be Heaven or a “New Democracy,” never mind if it is spiritually ugly and immorally “won” and taken from someone who is already there, has made a citifying world of people who, unconscious of it, have become our own ogreish problem to ourselves, our future, and the world. This is a problem that we cannot continue to attempt to competitively outrun by more and more effectively designed technological approaches to speed away from the past, for the specter of our own earth-wasting reality runs grinning competitively right alongside us. By developing even more effective and entertaining methods of escape that only burn up the earth, the air, animals, plants, and the deeper substance of what it should mean to be a human, by competing to get ahead, we have created a brakeless competition that has outrun our innate beauty and marked out a very definite and imminent “finish” line.

Living in and on a sphere, we cannot really outrun ourselves anyway. Therefore, I say, the entire devastating and hideous state of the world and its constant wounding and wrecking of the wild, beautiful, natural, viable and small, only to keep alive an untenable cultural proceedance is truly a spiritual sickness, one that will not be cured by the efficient use of the same thinking that maintains the sickness. Nor can this overly expensive, highly funded illness be symptomatically kept at bay any longer by yet more political, environmental, or social programs.

We must as individuals and communities take the time necessary to learn how to indigenously remember what a sane, original existence for a viable people might look like.

Though there are marvelous things and amazing people doing them, both seen and unseen, these do not resemble in any way the general trend of what is going on now.

To begin remembering our Indigenous belonging on the Earth back to life we must metabolize as individuals the grief of recognition of our lost directions, digest it into a valuable spiritual compost that allows us to learn to stay put without outrunning our strange past, and get small, unarmed, brave, and beautiful.

By trying to feed the Holy in Nature the fruit of beauty from the tree of memory of our Indigenous Souls, grown in the composted failures of our past need to conquer, watered by the tears of cultural grief, we might become ancestors worth descending from and possibly grow a place of hope for a time beyond our own.

Any of us born into the competitive warlike commercial conditions of modern life probably have our heads invaded by the distant gruntings of the scared urgings of civilization’s hard-faced Coach screaming, “You’re nothing, you’re nothing, you’ve got to win to be something, outrun your nothingness, run, win, be someone, outrun the next guy, outstrip the hungry debts of our cultural past!” But deeper and wider inside the vast wilderness of the territory of our forgotten Indigenous Souls, a place not understood and regarded as nothing by the Coach, there courses along in its own special way a valuable beautiful runner whose rhythmic puffing and gorgeous able motion keeps the Sun and Moon rolling, our hearts beating, the lizards grinning, the whales dredging the soggy sand of krilly oceans, the world jumping, living, dreaming, flying, whose dusty drumming friendship of feet on natural earth does not run to get ahead or away but to come home again to feast with the rest of our hearts and souls. And strangely enough, even the Coach must eventually straggle in for even he must eat, and of course, when it comes to the thinking of the Indigenous Soul and the generosity of seeds, there is always an empty chair waiting for even him at the feast table.