Guest post by Uwe Blesching

This article was based on research conducted for The Cannabis Health Index: Combining the Science of Medical Marijuana with Mindfulness Techniques to Heal 100 Chronic Symptoms and Diseases, and first appeared in CHI Magazine, available for download here.

The door of the twin jet airplane, flying under the flag of the the black star (now long gone to the metal equivalence of the elephant graveyards), swung open and wide. I stepped through the aluminum door and ran into a solid wall of heat. It was the time of Harmattan. The seasonal, hot, dry, and dust-laden trade-wind blew straight from the North, the Sahara. All at once it offered a feeling of a relaxing caress… and the subtle stress that comes from instantly throwing the body’s temperature control system into overdrive.

I had been looking forward to this trip—no, I had been obsessed, wanting to learn more about natural prevention and treatment protocols for mankind’s age-old enemy, malaria. Most of the information in Europe or the U.S. available on this topic, based on the efficacy of pharmaceuticals, was unsatisfactory and theoretical. I wanted practical information. Where better to learn, I thought, than in malaria-endemic regions, and from physicians and alternative healers with actual knowledge and experience?

Now, for the first time in my life, I was in Ghana. Accra, the port city and capital, was opening another set of her doors into and through the narrows of custom lines and the border ritual called passport control. The architecture of the airport buildings made use of the wind, keeping the lines of weary but excited travelers cooler and protected from lingering insects. One at a time, the airport door released us into the adjacent plaza.

We were greeted by a sea of waiting people undulating gently in primary colors and apparently impervious to the brightness of the light and extreme heat. At first my mind couldn’t make sense of the experience: many people waiting for so few of us arriving passengers. I gazed at the masses of smiling people dressed in both modern and much more traditional attire. There, I saw a sign with my name on it, held up high by a handsome man with a contagious and friendly smile. I smiled back and made a beeline straight toward him.

It was Jojo, my local contact, guide, and consultant about all things African. As I quickly discovered Jojo was an active member of a Pentecostal church, a fact that appeared to be confirmed by the omnipresent business signs in Accra that contained the word Jesus, holy, or a bible passage or numeration. His father, who had been a UN Ambassador of Ghana, was stationed in New York where his sister Maame still lived. Maame, an old friend of mine, had arranged the introduction. And now, I was in Ghana and I was in Jojo’s hands.

After settling, we began making appointments with government officials and obtaining permits, making plans and itineraries to explore the Ghanaian plethora of natural and pharmaceutical methods of preventing and treating malaria. Ghana’s link to traditional medicine is strong. The country has rich and diverse herbal healing traditions informed by time-proven roots and expressed in more than seventy different tribes and as many languages or dialects. The most prominent is the Akan ethnic group, which is further divided into the Ashanti, Kwahu, Fanti, Akyem, and Akuapim.

However, just because a practice was old or still in use did not necessarily mean it was effective or even practical. For instance, the fat of a boa constrictor was said to be good for gout when a simple restriction of meat would yield much better results (not to speak of the countless boas saved to roam the wild). The challenge was to discern “snake oil” from the prevention method or treatments that worked. For this distinct purpose, the Ghanaian government created the Traditional Alternative Medical Directorate (TAMD).

With collaboration of the World Health Organization (WHO), research centers like the Center for Scientific Research into Plant Medicine in Mampong (a prominent Ashanti village), 280 long and hot kilometers north of Accra, are steadily evaluating traditional treatments used by local indigenous healers for as long as anyone can remember.

When such treatments are found effective and safe, they are produced, promoted, and offered to those in need through local traditional clinics, as well as by pharmaceutical multinationals who are only painfully aware of the ever-growing resistance of malaria to the few still-functioning prescriptions drugs.

This collaboration has led to new protocols, such as artemisinin-based combination therapies that utilize wormwood a common, bitter Chinese weed alongside a pharmaceutical like mefloquine (which on its own has lost much of its potency to destroy the parasite), thus saving countless lives in the process (not to speak of the enormous profits rained upon Big Pharma). Consider the cost of a single treatment of mefloquine alone about $50 (USD) at the cheapest pharmacy even without a more effective herbal combo approach. Now multiply this by the many millions of locals and travelers who rely on it for protection or treatment, and you begin to see the vested interest of the multinationals.

Now, as much as I loved how an indigenous healer’s knowledge about a single Chinese weed has saved perhaps thousands from a horrific fate (well okay, shareholders are happy too), what really blew my socks off was yet to come.

The next day back in Accra, Jojo had arranged a visit to Aponche Clinic. Aponche is the only working, traditional bonesetting clinic in Accra, Ghana. Among its reputation for being able to set bones that even the local military hospital and its team of well equipped and trained orthopedic surgeons could not set, they also produced a natural concoction to treat malaria.

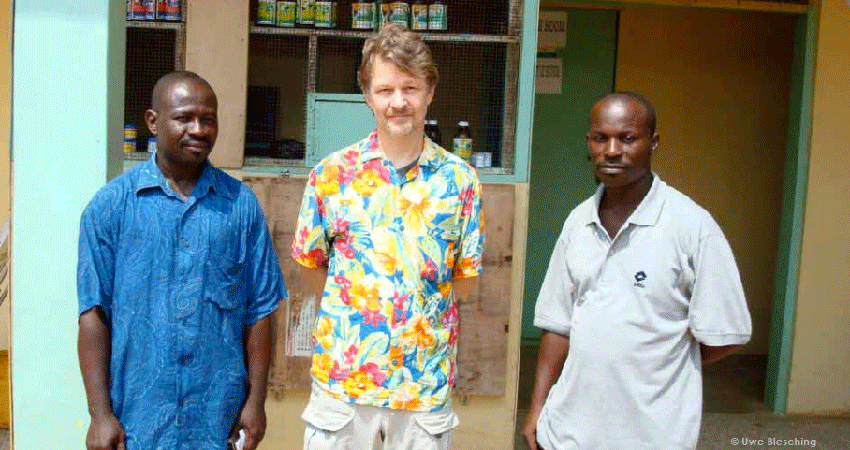

That early morning, we left the city center and our driver expertly navigated the busy traffic into the outskirts of Accra. A long driveway led to an unassuming and fading yellow one-storied building comprised of a couple of wings and a small construction site. A couple of people were busy pounding herbs and a couple of others were busy applying plaster to a yet-unfinished wall. Jojo displayed his signature smile that reached from ear to ear when he announced that part of the daily healing regimen at Aponche included a Lord’s Prayer. He warmly introduced the resident bonesetters, two shy, kind men in their late thirties or early forties, and without much delay I was given a tour of Aponche. Finally, a chance to explore their secret recipe for malaria, and my firsthand look at preparations of natural plant ingredients made into a concoction to treat it. After all, this is what I had travelled thousands of miles to explore.

However, to my surprise, my focus quickly shifted to the dozens or so patients recuperating from all kind of fractured bones. I had been a paramedic for more than twenty years in the very busy city of San Francisco. From the seedy, tough-ass Tenderloin to the ever foggy-seeming Richmond district, to the simple, single home bungalows at the Cow Palace to the fancy villas at Coit Tower, I had seen, treated, and set my share of broken bones. But what I saw here really blew my mind: a radical approach to healing fractures. I had been trained in the orthodox medical paradigm where a broken bone is set, realigned manually or surgically, and than placed into a semi-permanent cast for a period of 3 to 10 weeks (depending on location of fracture and age of the patient), the idea being that the fracture must remain undisturbed to heal. However, there is a downside to semi-permanent casts that was revealed by a study conducted on more than 200 pediatric patients (average age of 8) by the University of Maryland School of Medicine (2014). Researchers discovered that a whopping 93% of kids with fractures had iatrogenic complications (injuries caused by doctors or hospitals) arising from semi-permanent casts. Complications included “swelling (edema), skin breakdown (ulceration), and poor healing due to inappropriate fracture immobilization.”

Here at Aponche, bonesetters did what no western hospital would dare to do. Aponche used basic field casts that could be undone daily to check, re-check, and topically treat and massage the fracture sites and surrounding tissue. Daily checks without x-rays? Massaging a fracture site while the healing was in progress? Applying topical plant constituents (that appeared to be a gooey mess of a mud-like substance) to the damaged tissue as often as needed? My sterility-focused mindset got to take a break. Instead, I was invited to examine something new and very counterintuitive, something that challenged my modern medical training to the core.

I toured the clinic and was introduced to each patient, heard each’s story. One after another told me what happened, how their bones, spine, arms, or legs were shattered by one or another horrific accident, their harrowing tales of how they each made it to the outskirts of town with dangling limbs until they arrive at the clinic.

For instance, Michael, a fit young man in his early twenties, had been playing soccer and sustained a kick to his shin so hard that it left his tibia and fibula (shin bones) protruding through his skin. He was taken and treated at the modern, western hospital, the VA in Accra. After the cast came off, the skin above the fracture site had healed, but his bones had not set and his lower leg was left dangling (the nightmare of any fracture patient as well as his or her orthopedic surgeon).

Without much fanfare, his mother took him to Aponche. The bone was set once more and placed in a temporary cast. He received daily treatments of touch, a topical poultice containing a combination of spices, and local herbs that were placed on a single-layer plastic bag (as a moisture barrier) that was finally wrapped with a common, flexible bandage. And twice a day he was given the clinic’s own herbal concoction for pain and healing. After about two weeks, the bones began to finally set. He was seeing the light at the end of a long tunnel.

As was I. We finished the rounds and we finally went to the part of the clinic that made the concoction for malaria. The very little and dimly lit room contained numerous dry and fresh herbs. It smelled good, but like nothing I ever smelled before. I asked about the specific ingredients that the clinic had been using to prevent and treat malaria patients. And, while the bonesetters at the clinic were willing to share some of the ingredients, the exact list was kept a secret…the elder of the bonesetters solemnly pointed out that “too many times the white man has come and stole medicinal knowledge, made billions, and shared none of it with those who discovered and generously shared them in the first place.” Wow. After a long pause of silence… I laughed to myself; I completely understood.

The few ingredients the bonesetters were willing to discuss were similar to the ones used in the healing of fractured bones. They were local spices (rare in the western world), many of which are rich in a compound called beta-caryophyllene, chiefly among them black and white Ashanti peppers (Piper guineense) and alligator peppers (Aframomum melegueta).

It wasn’t until many years later, when I was writing The Cannabis Health Index (CHI), that I learned that beta-caryophyllene has the capacity to signal endocannabinoid receptors (CB2) and, in doing so, initiate a host of beneficial and therapeutic actions that speed the healing process. For instance, once CB2 is activated, a number of biological changes take place in the human body that at once strengthen the body’s immune system, reduce even severe inflammation and swelling, stimulate deep wound healing, and even produce some analgesic effects (for more information, read Dr. Busses’s article “Of New Worlds, Of Heroes, and Sidekicks”).

A new study conducted by a team of international researchers from Israel, Switzerland, and Sweden just published (2015) in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research may also suggest a mechanism that helps explains Aponche’s success rate. The team discovered that CBD, another primarily CB2-activating non-psychoactive cannabinoid, had the capacity to make fractured bones stronger while they heal (“enhancing the maturation of the collagenous matrix, which provides the basis for new mineralization of bone tissue”) and thus not just strengthen fracture sites, but speed the healing process itself and make it harder to break in the future.

And, while this story must come to an end, another surprise is worth mentioning, and maybe worth a tale all and by itself. One thing that I always hated about medicine in the U.S. was the lack of universal health care. Being German, I grew up where worries about money for the sick and injured do not exist. So, Aponche surprised me once again when I learned that treatment began instantly and without the worries of money (who knows how to measure the healing influence of not having to worry about sky rocketing bills). Aponche takes donations or payment, but no treatment is refused for lack of money. As I settled into my uncomfortable airplane seat and left Sub-Saharan Africa behind me, I couldn’t help but think of what happens in the tiny, dimly lit malaria medicine preparation room. I put on the cheap earphones and tuned into the movie in front of me. I laughed out loud (which rather unpleasantly surprised my co-passengers) when I heard the words “life is like a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re gonna get.”