The Martial Arts as a Spiritual Pursuit (Part Two)

Categories: Fitness & Sports Martial Arts

Guest Post by Walther G. von Krenner and Ken Jeremiah

The following is the second segment of a two-part series by Walther G. von Krenner and Ken Jeremiah who, along with Damon Apodaca, co-authored the book Aikido Ground Fighting: Grappling and Submission Techniques.

You can read part one here.

The Martial Arts as a Spiritual Pursuit (Part Two)

Ueshiba Morihei (1883-1969) said that Aikido is not a martial art; it perfects and completes all other arts. A spiritually-inclined person, he clearly perceived Aikido as something universal. He similarly said that Aikido is the Path that is not a Path; it joins all other Paths. In a sense, this can be said about any art form that leads to spiritual advancement. Many paths lead up a mountain, but there is only one summit. People may begin in different places, facing diverse difficulties along the way, but if they stick with it, they will eventually be together at the top, with the same understanding. In this way, martial artists, priests, carpenters, painters, sculptors, writers, and calligraphers alike can achieve the same level of spiritual understanding. It doesn’t matter what career or hobby you take up, if you approach it in the correct manner, it can lead to enlightenment.

Some people recognize certain Paths as inherently spiritual, but they should strive to recognize the transcendent aspects of seemingly non-spiritual arts. Such consideration will lead to better self-understanding. Practitioners take up the so-called spiritual Paths because they think they will make rapid progress. However, true insight cannot be rushed, nor does it suddenly appear. Students must train hard, devoting themselves to understanding the principles inherent in any art’s techniques. Ueshiba said, “Within the varied techniques is deep meaning.” Comprehending the profound significance that each technique is meant to convey takes decades.

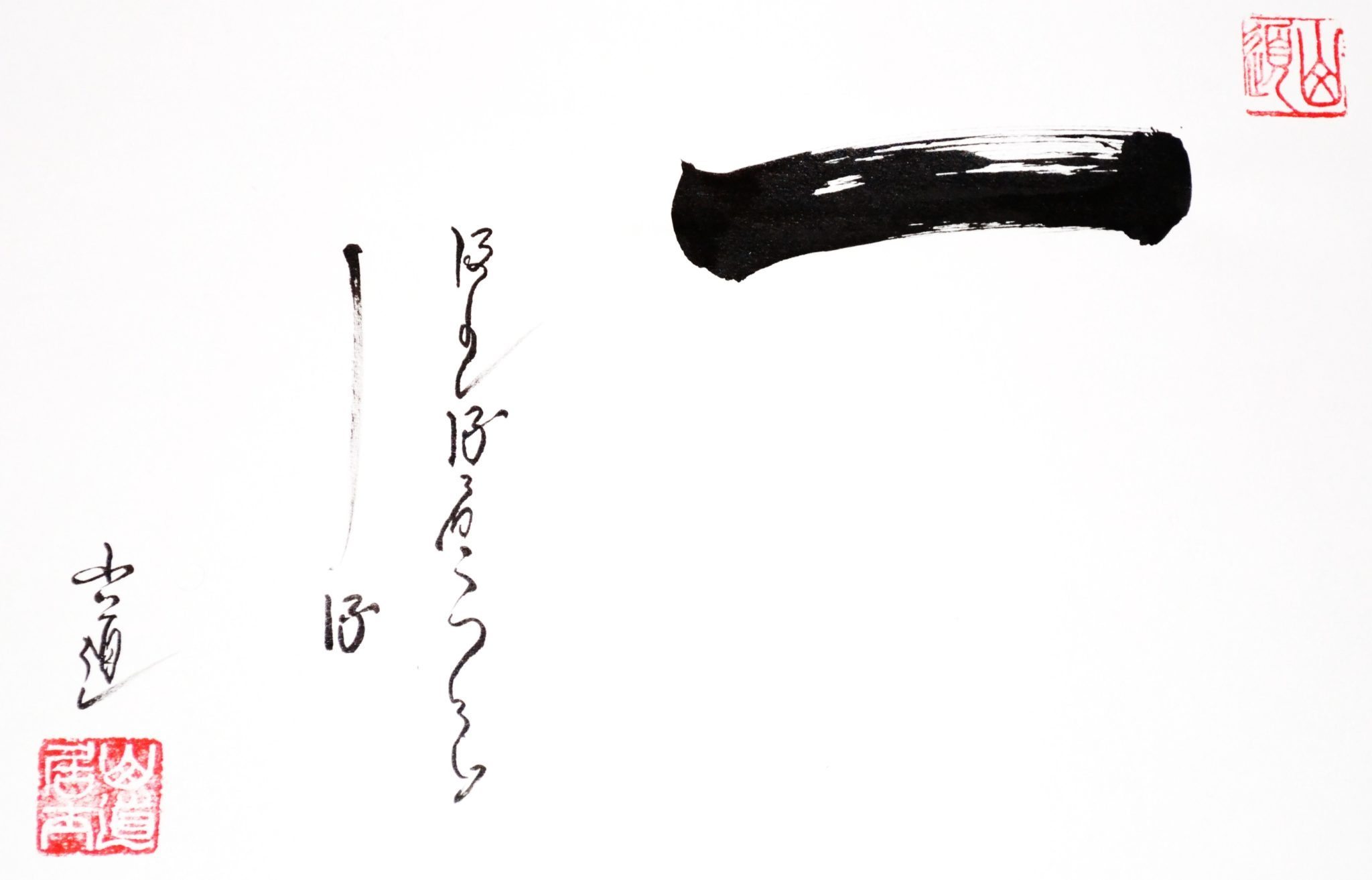

In the martial arts, students enter the dojo and learn basics skills: how to tie their belts, how to sit and bow, and how to use the art’s terminology. Then they learn how to stand and move correctly before studying basic techniques. At first, some will struggle with the movements because they seem unnatural, but after enough time has passed, students will begin to feel successful. Others who have better proprioception might think that they are able to duplicate the instructor’s movements in no time at all, but their techniques are ineffective when applied to a resisting training partner. Their angles might be incorrect, their centers unstable, and they have not yet developed power. Even though the outer form might resemble what the instructor demonstrates, the real principles behind them have yet to be perceived, so skill is lacking. When students learn Japanese calligraphy, they often begin with the number one, which in Japanese (and Chinese) is just a horizontal line. They study their teacher’s stroke and try to duplicate it. Sometimes, pupils think they have it right away, because they misunderstand the term “duplication.” It is not a matter of writing ichi, which even untrained people could accomplish immediately. It is replicating the ink’s thickness, the applied pressure, and the energy behind it. They must learn to see the white specks within the black, the trailing ink deposited from individual brush hairs; and then they must copy it. Exactly. This is not an easy thing to do, but the pursuit of such perfection imparts true skill.

"Ichi: The Number One" Students must duplicate all aspects of the calligraphic stroke.

In the martial arts it is the same. Students must strive to copy their teacher’s techniques: not just the techniques’ appearance but also their feel. The subtle pressure changes and sensitive body movements must be felt, studied, and then practiced. Students will fail constantly. There is no way around this. It is said that masters are only successful because they have failed more times than beginners even try. This is certainly the case in any endeavor worth pursuing. For the next several years (or more), students continue to perfect their techniques. Throwing and pinning others, in addition to being thrown and pinned, they learn what works and what does not. Their skills improve. At this stage, practitioners become confident. They believe that they are good, and as soon as this happens, their progress stops. Sagawa Yukiyoshi (1902-1998) explained, “As soon as you think you are good enough, you will hit a dead end. You will stop growing right there.”

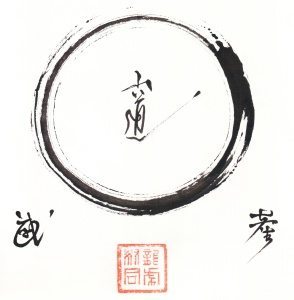

As long as people remain open to new ideas and perspectives, they will acquire new insights. People who think they are skilled or wise will never really be skillful nor knowledgeable. Those students who will one day master the art’s physical aspects continue forging themselves. Gradually, their pride vanishes, and although they do not view themselves as experts, new students admire and emulate them. They become role models, even though they never sought to become such exemplars. Such practitioners do not stop. They continue training with no end in sight. They do not train to reach a goal, but only for the sake of training itself. For them the Path has become the destination, so it ceases to exist. The Great Path is really no path.

"Enso" This represents a circular journey, among other things.

This is represented as a circle, called enso in Japanese. A famous Zen parable mentions a man seeking enlightenment (satori in Japanese). He meditates daily with no noticeable progress, so he decides to leave home. He travels to distant places and sees things he couldn’t have previously imagined. Piling experience upon experience, he becomes much wiser than he ever could have dreamed, yet it still seems that enlightenment is far off. He trains under Zen masters and learns from those who have made substantial spiritual progress, yet he still does not attain his goal. After years, he admits defeat and returns home. Upon entering his abode, enlightenment suddenly dawns upon him. He ponders his travels and exclaims, “I have traveled to distant places, searching for something that has been here, with me, the entire time. It would’ve been better to have been deaf, dumb, and blind from the very beginning.”

He is back where he started, seemingly the same person, but he is different. Enlightenment did not appear because he was back at home. It occurred because he set out on a long, arduous journey seeking it. However, he only found what he was looking for when he stopped searching. It is the same in the martial arts. Practitioners do not gain spiritual understanding while trying to become stronger than their potential adversaries. Such understanding occurs after they have surpassed this stage and realized that there is no end. They no longer aim for anything in particular, but they have forged themselves through decades. Ueshiba Morihei wrote, “Iron is full of impurities that weaken it; through the forging fire, it becomes steel and is transformed into a razor-sharp sword. Human beings develop in the same fashion.”

No matter what you do, devote yourself to it. Do not train to get something. Train for the sake of training itself. In time, you will master the physical movements, and you will begin to understand the self. The ox-herding pictures in Zen represent this journey, and deep meaning hides in the paintings. In the first one, a man seeks the ox. In the second, he discovers footprints. Then, he perceives the ox, catches it, tames it, and rides it home. In the ninth frame, he returns to the source, where he experiences complete awakening (satori). Finally, he returns to the world.

Obviously, the ox is a metaphor. Although explanations that are more accurate could be offered when considering a particular path, this is how the 10-Bulls or ox-herding pictures relate to life itself: First, you may wonder why you are here. Searching for meaning, you realize that there is more to life than physical and material things. This leads you to discover that life has a hidden significance, which in turn forces you to discover your life’s purpose. Once you have fixed your mind on this purpose, you strive to discover how to fulfill your destiny. When you know what to do, you do it. You walk the Path. Then, as you approach its culmination, you realize that the Path itself was unimportant, just a means to an end. You then realize that you are not who you think you are; there is a higher self, which is the real “you.” You comprehend that your true nature is part of the universal essence, which the divine spark of life rests within. Finally, you return to the world and benefit all those around you.

Now that you know what to do, breathe deeply and clear your head. A long path stretches in front of you. It is time to take that first step!

About the Authors

Walther G. von Krenner has been studying Japanese martial arts since 1957. He trained in Japan at the Aikido Hombu Dojo while the founder Ueshiba Morihei was alive, and he continues to teach in Kalispell, Montana. More information about him can be found at http://kalispellaikido.net. Ken Jeremiah writes about spiritual and religious phenomena. His website is www.kenjeremiah.com. Together with Aikido instructor Damon Apodaca, they have coauthored Aikido Ground Fighting. Other books about spirituality and the martial arts are forthcoming.

(c) 2015, Walther G. von Krenner and Ken Jeremiah

Tags: Japanese Martial Arts Self-Improvement & Inspiration Aikido Ken Jeremiah Walther G. von Krenner