In addition to the limited odd jobs Abe was able to do at such a young age and her time spent scavenging for food, her days were also occupied by taking care of her father and keeping up with the constant maintenance of their rondavel, a one-room hut made of cow dung. Every year, she begged him to allow her to go to school, but each year he said no, insisting that women and girls belonged in the home.

Despite his flaws, Abe loved her father and didn’t want to defy him. But she was determined to get an education, and at fourteen she finally went to the village chief for help. He convinced Abe’s father to allow her to attend school as long as she kept up with her other responsibilities. Abe was ecstatic that, at last, she had the opportunity to get an education! But even from the very beginning, the experience tested her determination. She writes about her first day:

To start the day, a teacher took all the first-graders and asked them what they wanted to be when they finished school. “I want to be a nurse,” I said when it was my turn. He looked at me, incredulous at first, and then burst out laughing. “Now here is a child! How old are you?” “Fourteen.” “And you want to become a nurse?” “Yes.” Now, all the students joined in laughing, and the teacher wrote what I said on a piece of paper and handed it to me. “Go to this-and-that class,” he said, “and give it to your teacher.” So I did, and when the teacher saw that note, he too started laughing and mocking me. I remember the entire class laughing and laughing as if they had never heard anything funnier. They figured I would be in my mid-twenties before I could even start high school and so a nursing degree would probably take until my mid-thirties. Considering that girls usually married around age sixteen, this idea seemed impossible to them. I was hurt, but I remembered something my father once told me: “When people laugh at you, it’s because they only see the outside, they don’t know what’s inside you.” Well, the class knew my age and understood the math of my situation correctly, but I guess they didn’t know what was inside me.

During nursing school, Abe adopted four children—something completely unheard of for unmarried black women to do at the time. She saved each of them from tragic situations (worsened by Apartheid) and raised them into adulthood. Years later, when the AIDS pandemic hit, she saw no other option but to do this again, and again, and again. She took in every orphaned child she had room for, and then secured a larger home so she could continue to take them in, and found more assistance so that each had individual care and attention.

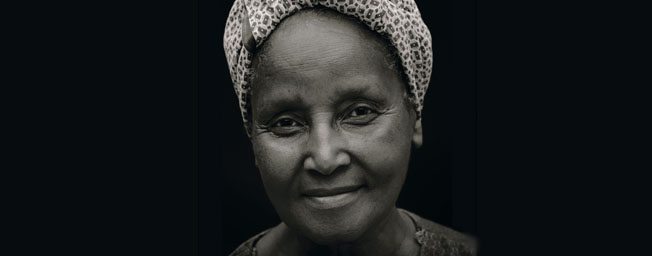

In her eighties now, Sister Abe has retired from nursing and dedicates herself entirely to raising children, making sure that each is educated and empowered. In honor of Women’s History Month, we want to share the dreams of some of her teenage girls, which she made possible by taking them in. Listen for the commonality among their aspirations, and take a minute to think of how far one woman’s incredible determination and seemingly endless compassion will continue to ripple through their community and beyond.

Kulungile Dreams from Dharmagiri on Vimeo.

Ubuntu is a really beautiful way of looking at things. It is the Zulu understanding that you are a person because of other people, and it is the reason for your helping others and others helping you. It’s really a very old idea that started long before industrialization. We have a saying in Zulu that one hand helps the other. If you want to wash one hand, the other hand needs to help. Ubuntu is not a moral obligation; rather, it’s a natural sense that we are all in this together, a sense of belonging to a community, that by doing for others, you help yourself.

—Sister Abegail Ntleko

Sister Abe’s memoir Empty Hands is coming out on September 1, 2015. Stay tuned for more details.